Contemporary painter Wu Guanzhong once beautifully noted, “There are two great things in tradition: the white of Xuan paper and the black of lacquer.” This perfectly encapsulates the unique value of “Chinese Traditional Lacquer Craftsmanship” and “Chinese Traditional Painting” as exceptional cultural heritage. Lacquerware painting, the ultimate fusion of these two art forms, carries the exquisite techniques of traditional lacquer craft while belonging to the traditional painting system, offering a vivid portrayal of China’s artistic spirit and aesthetic sensibilities. As of 2020, the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list proudly includes fourteen distinct lacquer crafts from China, such as “Chengdu Lacquer Art,” “Xiamen Lacquer Thread Carving Technique,” and “Fuzhou Bodiless Lacquerware Coating Technique,” collectively highlighting the profound significance of “lacquer” as a symbol of Chinese national culture.

China holds the distinction of being the first nation globally to recognize and utilize “lacquer.” Archaeological findings reveal that the 8,000-year-old lacquer bow unearthed from the Kuahuqiao site, featuring a sang (mulberry) wood core entirely coated in red lacquer (appearing blackish-brown due to post-excavation oxidation, excluding the grip), marks the earliest documented use of lacquer in China. The “vermilion lacquered large bowl” from the Hemudu culture, dating back over 7,000 years, further attests to the enduring history of Chinese lacquerware. The paintings adorning traditional lacquerware, akin to other forms of intangible cultural heritage, are deeply intertwined with the unique lifestyle and humanistic thought of the Chinese nation, comprehensively reflecting the cultural landscape of different developmental periods and rightly deserving the title of a “living fossil” of Chinese culture.

Han Dynasty lacquerware painting, utilizing lacquerware as its canvas, conveys a rich tapestry of Han Dynasty cultural information, spanning politics, economy, philosophical thought, religious beliefs, aesthetic psychology, and numerous other dimensions. Simultaneously, through its distinct expressive medium and extensive image system, it showcases the artistic forms of Chinese painting and the unique spirit of Chinese lacquer art, establishing it as an invaluable traditional culture that the Chinese nation must both inherit and promote. However, the multifaceted impacts of modern industrial civilization, the advancements in information technology, and the influx of foreign artistic trends have gradually led to a discernible decline in traditional lacquer art and lacquerware painting.

Over the past four decades, China’s economy has witnessed remarkable growth, becoming the world’s second-largest. Nevertheless, the evolution of social systems and ideology and culture has relatively lagged, giving rise to various societal challenges. As the proverb wisely suggests, it is now imperative for us to pause our hurried pace and allow our souls to catch up. Both modern civilization and traditional culture represent the culmination of human labor and wisdom, the harmonious union of the material and the spiritual. A respectful and informed engagement with traditional culture serves as a critical measure of a nation’s maturity, confidence, and rationality. The contemporary creation of lacquer paintings often lacks a strong national and creative spirit, stemming from an insufficient grounding in the profound connotations of traditional culture. Consequently, a “return” to the Han Dynasty, an exploration of the Han people’s deep connection with lacquer, and an experiential engagement with their artistic spirit and character through exquisite lacquerware paintings have emerged as vital pathways for us to embrace our heritage and rediscover our identity. This endeavor holds significant historical value and offers a crucial impetus for innovation in the research and creation of contemporary lacquer art.

The Wellspring of Lacquer: A Cultural Symbol Enduring for Millennia

The character for “lacquer” in ancient texts was also written as “桼” (qi). Investigations reveal that numerous place names derive from the local abundance of lacquer trees, such as “Qiyuan” in Tongchuan. The nomenclature of lacquer varies according to its origin, including Shu lacquer from Sichuan, Dafang lacquer from Guizhou, Niuwang lacquer from Shaanxi, Maoba lacquer from Hubei, and Puxin lacquer from western Hubei. As the first nation globally to recognize and utilize lacquer, China still accounts for over 85% of global lacquer production, unequivocally establishing lacquer as a quintessential symbol of Chinese culture.

Lacquerware: An Artistic Synthesis of Utility and Aesthetics

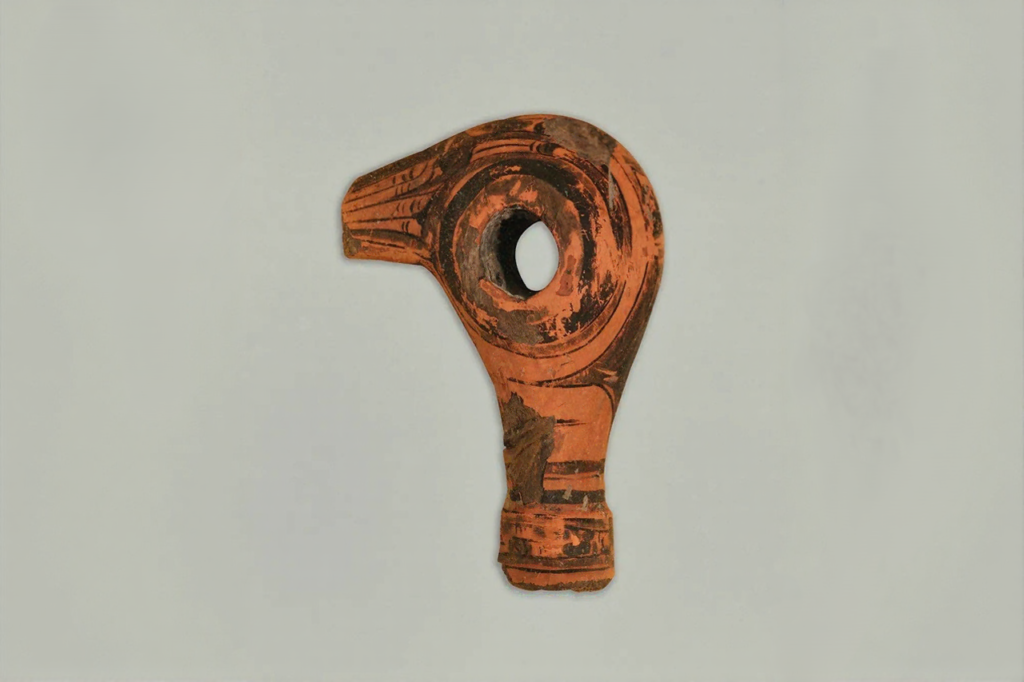

The term “lacquerware” first appears in the Old Book of Tang, Biography of Chu Suiliang: “Shun made lacquerware, and Yu carved his sacrificial stands.” Prior to this, historical texts predominantly employed “ren qi” or “shi qi” as general terms for lacquerware. Contemporary understanding of lacquerware broadly encompasses objects with a lacquered surface. The earliest extant examples include the 8,000-year-old “lacquer bow,” the 7,000-year-old “vermilion lacquered wooden bowl,” and “red lacquered bamboo sword handle fragments” from the Daxi culture. The excavation of these Neolithic lacquerwares underscores their integration into the daily lives of people during the prehistoric civilization period.

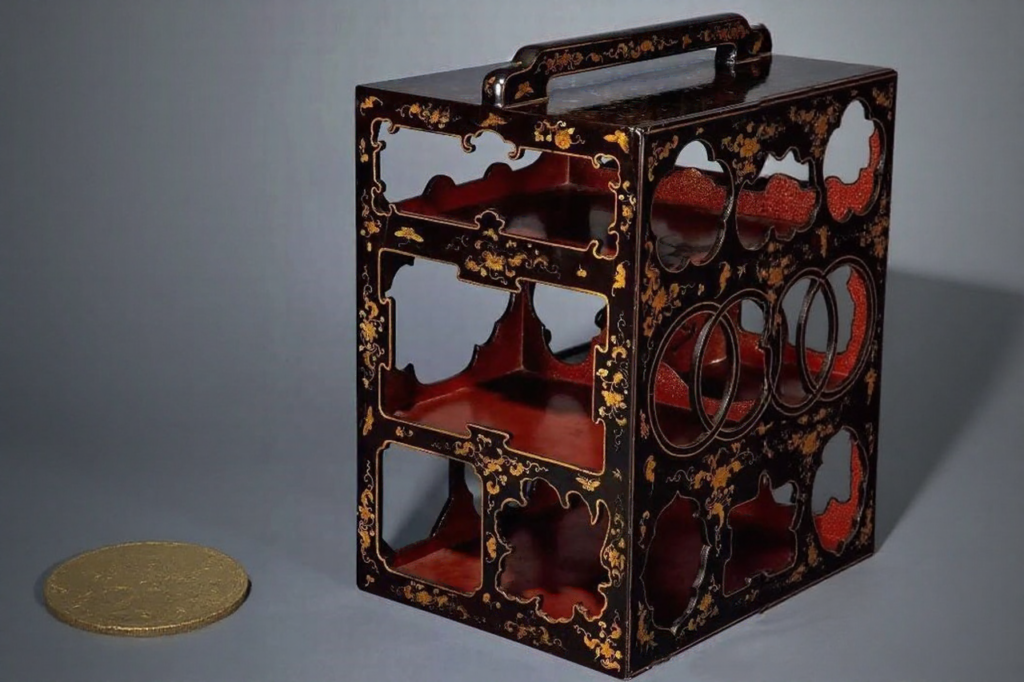

Lacquerware possesses numerous unparalleled characteristics compared to other materials. Predominantly crafted from wood, it exhibits corrosion resistance, ease of preservation, and robustness. Its lighter weight compared to bronze and ironware facilitates transportation. The body-making process allows for the full expression of craftsmanship and the ingenuity of lacquer artisans, while the lacquer surface provides a canvas for unrestricted painting and decoration. The decline in bronze ware production during the Han Dynasty, coupled with the nascent development of utensils made from other materials, significantly propelled the flourishing of lacquerware. Lacquerware played a vital role in the daily lives and funerary rituals of the Han people. Emperor Wen of the Western Han Dynasty, advocating for “simplicity and frugality,” issued a decree: “The construction of Baling should entirely utilize pottery; gold, silver, copper, and tin are not permitted as decorations, and no elaborate tombs should be built, intending for economy and avoiding extravagance.” Consequently, Han tombs often lack gold and jewelry but abound in lacquerware reflecting the lives of the nobility.

Archaeological discoveries of Han Dynasty lacquerware are extensive, with representative sites including Han Tomb No. 1 at Dafentou in Yunmeng County, Hubei Province; Han tombs at Fenghuangshan in Jiangling; Han tombs at Tangjialing and Mawangdui in Changsha, Hunan Province; Han tombs at Shilibian, Dongfeng Brick Factory, the tomb of Shi Qi Suan in Haizhou, the tomb of Dongyang in Yutai, and the tomb of Marquis Haihun in Jiangxi Province, as well as Han tombs unearthed in Guizhou, Sichuan, Anhui, Shandong, and Shaanxi. Han Dynasty lacquerware, in terms of form and production techniques, both inherited from previous eras and introduced new developments. This period witnessed a rich variety of lacquerware types, including both everyday utensils and funerary objects. The use of jia zhu tai (cloth-wrapped lacquer bodies) increased, painting skills further matured, and the inlay decoration technique reached its zenith.

Lacquerware Painting (Lacquer Painting): An Artistic Legacy Spanning a Millennium

Existing ancient literature lacks a definitive articulation of the concept of “lacquerware painting.” As an integral element of traditional lacquerware, lacquerware painting, in a broad sense, refers to images painted on lacquerware, generally termed lacquerware decorative patterns, ornamentation, or designs by scholars. Painting is defined as “an art form that uses colors and lines to depict images on a flat surface.” Certain images on Han Dynasty lacquerware already possessed the characteristics of painting and can be classified as lacquerware painting, or simply “lacquer painting.” “Han Dynasty lacquerware painting” specifically denotes artistic works among Han Dynasty lacquerware images that exhibit the artistic style of painting and possess independent aesthetic value. These works display certain spatial, narrative, symbolic, and other painting attributes, distinguishing them from decorative patterns on traditional lacquerware and also differing from the definition of “contemporary lacquer painting.”

Lacquerware initially served primarily utilitarian purposes. In ancient times, lacquerware painting was generally applied to the surface of lacquerware, emerging during the gradual transformation of lacquerware from purely functional objects to those embodying both practicality and aesthetics, thus becoming a component of lacquerware decorative art. However, the long-term use of lacquer by the ancient Chinese reveals that lacquerware painting was not solely confined to lacquerware as a base but also utilized pottery and metal. The painted pottery unearthed from the Kuahuqiao site, dating back 7,000 to 8,000 years, employed lacquer as a medium to mix and apply pigments, with decorative patterns including stripes, zigzag lines, and crosses, arguably representing the earliest examples of lacquer painting we have encountered. The lacquerware fragments discovered in the No. 1 Eastern Zhou burial of sacrificial victims (Warring States period tomb) in Langjiazhuang, Linzi County, Shandong Province, stand as the earliest extant lacquer paintings in China. The depiction features four symmetrical houses, twelve figures, four plants, four flying birds, and twelve chickens. The figures are divided into six groups by the houses, each with its own narrative, and the figure representations are lifelike with vivid postures.

The Han Dynasty marked the golden age for the development of Chinese lacquerware painting, witnessing an unprecedented abundance of “Han Dynasty lacquer paintings.” Historical records also contain numerous accounts of lacquerware painting, such as the passage in the Later Han Dynasty Prose, Ying Jie: “During the Yanxi period (158-167 AD), the elders in the capital all wore wooden clogs, and when women first married, they made lacquerware painted clogs with five-colored straps.” Another example is the lacquer plate unearthed from the Xinmang tomb M104 at Baonüdun, Yangshou Township, Xingjiang County, Jiangsu Province, which bears an inscription stating: “In the first year of He Ping (28 BC), supplied by the workshop, lacquerware painting craftsman Shun,” indicating the commonality of lacquerware painting at the time. Bamboo slips unearthed from the Mawangdui Han tombs in Changsha, which meticulously record burial items, include entries such as “six painted pots, all with lids” and “ten painted sheng containers.” Furthermore, among the over 600 lacquerware pieces excavated from this tomb, as many as one-third feature lacquerware paintings, the exquisite artistry of which is breathtaking.

“The Han Dynasty represents a significant turning point in the history of Chinese art. Prior to the Han Dynasty, paintings were essentially ‘appendages’ of objects, subservient to politics and utilitarianism. However, after the Han Dynasty, painting achieved aesthetic consciousness and became an object of beauty in its own right.” Han Dynasty lacquerware painting seamlessly integrated the inherent qualities of lacquerware with the essence of painting. In terms of composition, lines, and coloring, it already exhibited distinct artistic characteristics of independent paintings. This allowed “Han Dynasty lacquer painting” to function both as a constituent element of lacquerware craftsmanship and as a standalone artwork to be appreciated independently, akin to the paintings on silk and walls of that era.

Tracing the developmental trajectory of ancient lacquerware painting, traditional lacquerware painting reached its zenith during the Han Dynasty, gradually diminishing and eventually declining thereafter. Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, professional research and creation groups dedicated to lacquer painting, building upon the inheritance of tradition and the absorption of foreign influences, vigorously developed contemporary lacquer painting beyond the confines of lacquer art. In this new era, lacquer painting has been imbued with a contemporary definition: “Lacquer painting, as its name suggests, is a modern art form created using lacquer, a special painting material, in conjunction with other auxiliary materials.” In the 21st century, lacquer painting art has emerged from the heavy dust of history, establishing itself on a new historical footing. Confronting new lives and new phenomena, it will utilize its unique artistic forms and mediums to showcase the beauty of our present-day existence.

Although traditional lacquerware painting has experienced periods of prosperity and decline throughout history, the precious techniques, aesthetic principles, and underlying theories it encompasses warrant our in-depth study and inheritance. In the process of learning and inheriting tradition, the spirit of craftsmanship inherent in traditional culture should not be overlooked. It holds significant guiding importance for the creative spirit of contemporary artists. This spirit embodies honesty and love for work, the steadfast adherence to “never forgetting the original intention, in order to achieve the goal,” and the essential force that all research and creation groups must possess. Inheriting tradition is not a mere “return” to the past but rather, through the process of “recollection,” to contemplate and learn the essence of traditional works, allowing the ancient cultural treasure of lacquer art to radiate new vitality and vigor in the new era.